Hollywood as a lens to the American shadow

by Eivind Figenschau Skjellum

The US is a country that has not experienced foreign powers on home turf after its formation*. One would think this would lead the American mind to a place of harmony and peace. Yet, Hollywood moviemaking features an unmatched number of movies with invasions, presidential kidnappings, burning government buildings etc.

Why is it that Hollywood has such tremendous fascination with spectacular attacks on the USA, when, disregarding a few isolated examples, relatively few in number, they bear so little connection to reality? What can we deduce about the American psyche by really examining this odd phenomenon?

Come with me now on a journey of exploring this paradox.

Introduction

4th of July, 1776 was the day the Declaration of Independence changed the history of the world. It was a time of war and of a revolution in consciousness. For at this crossroads, the founding fathers authored a document that would not only lay the foundation for a new and great nation, but bring into being a consciousness the world had not yet known: The understanding that all men are created equal.

Ever since the signing of this revolutionary document, the United States has enjoyed a history remarkably free of real (not imagined) threat at home.

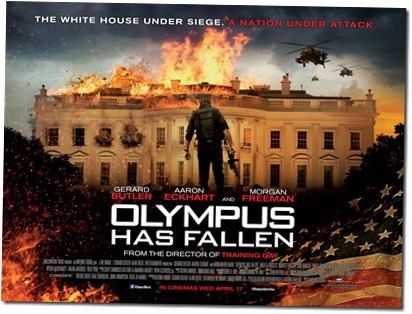

What I realized in a plane somewhere above Greenland recently was that Hollywood seems not to have noticed. Headed towards Washington DC, I watched two movies that featured presidents being kidnapped and evil powers invading or threatening from afar. The movies were GI Joe Retaliation and Olympus Has Fallen.

What I realized in a plane somewhere above Greenland recently was that Hollywood seems not to have noticed. Headed towards Washington DC, I watched two movies that featured presidents being kidnapped and evil powers invading or threatening from afar. The movies were GI Joe Retaliation and Olympus Has Fallen.

Whenever I’m on a transatlantic flight, I find myself in a liminoid space – as if I’m in a death process of sorts. And from that space of heightened awareness of the unconscious realm, this made no sense to me at all. It struck me as deeply paradoxical.

Shortly after my trip, White House Down was announced, its imagery and theme almost mirroring Olympus Has Fallen, further strengthening my desire to investigate.

The US: Origin story

The history of the US started in 1620 with a ship called the Mayflower. The vessel, en-route to New England, carried about a hundred people. They were largely Puritans who sought a life free from religious prosecution, but also craftsmen of all kinds. The white man had arrived on American shores. This time for good.

The history of the US started in 1620 with a ship called the Mayflower. The vessel, en-route to New England, carried about a hundred people. They were largely Puritans who sought a life free from religious prosecution, but also craftsmen of all kinds. The white man had arrived on American shores. This time for good.

What level of influence on contemporary American life does this ship and its passengers have? What does it mean that the first American settlers were pious people fleeing religious prosecution? It is hard to say. But I see today pious paranoia featured prominently in places such as Fox News. I don’t think it’s a coincidence. The passengers of the Mayflower set a precedence.

Then, in 1775, come the English. Greedy for power and control, they are not about to let this new and bountiful continent depart from the Commonwealth without a fight. But the French, Dutch and Spaniards intervene on the side of the 13 freedom-seeking American territories, and together, the coalition win the war. The United States is born. A new chapter in the history of the world starts.

And yet, however traumatic these events must have been to the fledgling US psyche, I don’t belive they fully explain the paranoia Hollywood displays in its moviemaking. Most European countries have been through hardships greater and more terrible than those of the US and yet their movie output seem to feature much fewer examples of these themes.

Searching for clues along the Washington Mall

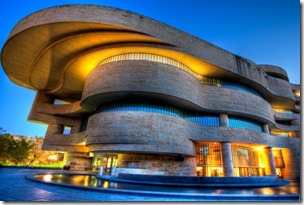

When I arrived at the Mall in DC, I was drawn particularly to the newest addition to the Smithsonian: The Museum of the American Indian. This is a beautiful building and a wonderful exhibition – worth a visit. Walking through its curved halls, studying the traumatic history of the American Indian, the flash of insight I’d had on the plane started crystallizing. What does it amount to in but a few words?

When the white man arrived in North America, he carried germs against which the American indian immune system had no defense. The germs effectively carried out a genocide, wiping out 90% of the Native Americans. NINETY percent. Just pause at the magnitude of that for a few seconds.

The white man had little trouble dealing with the remaining Native american resistance. In an effort to create a good life for themselves and their families, citizens of this new nation took the land from the Native American. And in just a few years, they managed to virtually wipe out the American Buffalo, the animal so sacred to the Native American, showing in the process, true to the Western industrial mindset, their horrific contempt of the miracle and mystery of nature and its inherent sacred order.

What happened was the start of great things. The way that it happened was very wrong.

What happened was the start of great things. The way that it happened was very wrong.

In observing this, something shifts in me and I’m pulled into a very deep place, one of unmourned dead, uncried tears, unshaken shakes, unshouted screams and unspoken guilt. A place which this museum puts us in more intimate connection with.

The deep place I’m tuning into is the same place of shadow and grief that has completely consumed Nathan Algren as The Last Samurai, one of the movies reviewed on this site, opens. He is traumatized, so guilty and ashamed for the terrible things he has done to the Native Americans. His superior Colonel Bagley, however, is not feeling any of that; he enjoys the emotional disconnection expected of any good soldier. Nathan, however, is not a soldier; he is a Warrior. And the actions he has carried out on behalf of the invading white man are hostile to his soul.

America’s curse

I have come to develop a deep fascination for and respect of the teachings of depth psychology (the branch of psychology which includes the unconscious).

In the process of deepening my understanding of the pervasive influence our unconscious minds exert on us, both individually and collectively, I have come to realize the importance of grieving that which was wrong and of discharing traumas. Whenever traumas are repressed, they fester. Eventually, they take us over.

The stealing of the United States from the American indian and the subsequent pillage and rape of the land which the American Indian considered sacred is a trauma that, as far as I can tell, has not yet been discharged. It has become shadow – the leper child stowed in the basement.

The stealing of the United States from the American indian and the subsequent pillage and rape of the land which the American Indian considered sacred is a trauma that, as far as I can tell, has not yet been discharged. It has become shadow – the leper child stowed in the basement.

American poet and founder of the Men’s movement Robert Bly has spoken much of this, of the repression of emotion that is required to live in this world as if it’s a place of sanity. He laments the lack of grieving in American culture. He laments the lack of grieving for the plight of the Native American. He laments the lack of grieving for the plight of the US war veterans, worshipped and idealized while still fit to represent heroic ideals, yet discarded the minute their bodies and minds take on the scars of war.

In observing all these Hollywood movies with stories of threats from afar and dark conspiracies from within, it may prove interesting to reflect on the following: The threat from afar was once the white man.

In the absence of fully feeling, grieving and discharging the impact of the plight of the Native American on the collective US psyche, protection mechanisms have been put in place.

One of these mechanisms is a powerful army. Its use in combat against a perceived threat conveniently distracts from the unhealed trauma at home.

Staying in conflict thus becomes an imperative.

A Warrior culture in need of a King

What do these movies with burning White Houses, exploding Capitol Buildings, kidnapped presidents and evil lurking in the shadows tell me? It tells me of a constant fear in the collective US psyche that the leadership of the nation, and thus the harmonizing force of the King archetype, will disappear, be corrupted or otherwise destroyed. The axis mundi is under threat, much like it once was for the Native American civilization.

What do these movies with burning White Houses, exploding Capitol Buildings, kidnapped presidents and evil lurking in the shadows tell me? It tells me of a constant fear in the collective US psyche that the leadership of the nation, and thus the harmonizing force of the King archetype, will disappear, be corrupted or otherwise destroyed. The axis mundi is under threat, much like it once was for the Native American civilization.

In observing that, I note that Hollywood voices a deeper truth – many Americans, like so many other people in the world, don’t feel safe. And in looking for the source of this pervasive sense of unsafety, many people, particularly the more conservative and ethnocentric, cannot bear to seek inside – for there waits the pain of the Native American trauma and a whole host of other repressed emotions. And so, they look outside for the nemesis, while heading for the nearest gun store flying the banner of individual freedom. Blinded by the hercules complex, they may call it courage. Though they would be wrong. It is the opposite.

If I wish to avoid confronting myself, I’d better confront another. Thus, I can feel safe in my identity as long as I have an enemy. Seeing that tendency in the American psyche puts the American obsession with being custodians of world peace, guardians of humanity, in new and troubling light.

The American world policing seems to come from a misplaced attempt at healing trauma as opposed to a place of empowerment. It seems a striving for redemption, partly fuelled, I believe, by an identity formed through heroic efforts in World War II, the last honorable war the United States engaged in, and partly through ethnocentric, religious zealotry.

As I alluded to above, a Warrior can feel on purpose as long as he stays engaged in conflict. There is something to fight for, something to rally around. Pausing to contemplate whether the fighting serves the transpersonal purpose essential to the mature Warrior is easily forgotten – any kind of fighting will have a Warrior feel alive.

But if there is no harmonizing King energy to facilitate the fighting, the acts of fighting become pointless, inevitably ending up destroying the world as opposed to defending it, much like the Buddhist myth of the crane and the crab (the crane is a symbol of the Warrior).

Hollywood’s constant display of the fragility of the American axis mundi should be of great concern. Without that axis mundi, a Warrior, like the crane in the myth, ends up eating the fish it swore to protect. And if we are to believe the myth, the crane gets its head clipped off.

Signs of our times, the building financial bubble being one of them, suggest that the head of the US is about to get clipped off. And with the pervasive influence ethnocentric, religious zealots have in the US now, that is something large parts of the world is rightly afraid of.

In the process of bringing the American leper child up from the basement into the light, we are running short on time. Hollywood movies like the Last Samurai and Dances with Wolves as well as the museum for the American Indian on the Washington Mall have made honorable contributions to this process.

But it’s not enough. In the act of constellating a strong axis mundi for the US and the rest of the world, we must all get busy, stepping into healthy leadership wherever we can.

The US story is the human story

If you have an anti-American bent, you may have felt a certain sense of glee reading this article. Watch out for that one. For this is not an American story, it truly is the human story. All across the world are countries where militarism, ego and paranoia are used to distract from the real issue. We have a world scene lacking in healthy King energy and it is our collective responsibility to address this situation.

I got a small taste of what that might mean for me when, on my trip, I had the privilege to share my views with an American woman trained as a Native American Grandmother. She nodded as I shared my views on Hollywood movies and their relationship to the Native American trauma and replied “I’m so glad you see that. Maybe you should tell someone about that.”

So I did.

*there was an incident with the burning of key government buildings in Washington DC by the English in 1814

Discuss the article below: