The Bechdel test: Application, historical context, and introducing a male equivalent

by Eivind Figenschau Skjellum

I write about men in movies. I write about how they can serve to inspire us to greatness.

Thankfully, there are also those who write about women in movies. Or rather the lack of women in movies. And when doing so, some tend to pull on the Bechdel-test.

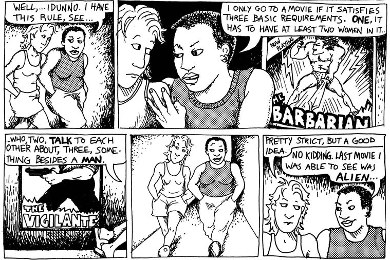

The Bechdel test was introduced by Alison Bechdel, an American cartoonist, back in 1985. Here are its humble beginnings:

A movie, as the cartoon tells you, passes the Bechdel test if:

- It has at least two women (with names) in it,

- who talk to each other,

- about something besides a man

The test has become very popular in feminist circles and recently Swedish cinemas announced that they will henceforth rate all movies using the Bechdel test.

In other words, the test has become politicized.

Applying the Bechdel test

The basic premise of the Bechdel test is that there are too few women in significant roles in movies. And there seems to be truth in that; According to Colin Stokes’s TED talk “How movies teach manhood” that I wrote about a few days ago, only 11 of the top 100 movies of 2011 had women leads.

Most movies featured on my site fail the test. Here’s a list of those who pass it (with a score of 3 out of 3), according to Bechdeltest.com:

- American Beauty

- Beowulf

- Eyes Wide Shut

- Revolutionary Road

- Lars and the Real Girl

- Mrs Doubtfire

- Robin Hood

- Sideways

- The 13th Warrior

- The Fisher King

- The King’s Speech

- V for Vendetta

Some of these pass it only just. So at least 12 of 41 reviewed movies pass the Bechdel test, which is almost 30%. A clear minority.

Some of these pass it only just. So at least 12 of 41 reviewed movies pass the Bechdel test, which is almost 30%. A clear minority.

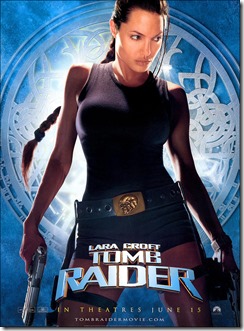

Here’s something puzzling though: A movie like Tomb Raider (which I haven’t reviewed) fails the Bechdel test. In fact, it absolutely flunks it (0 out of 3 points). So in other words, a female heroine with enormous courage making her way through a typically male-dominated environment scores no points. I understand that Lara Croft is not a well rounded, realistic female character that will serve as a positive role model to the young women of the world, but it still strikes me as peculiar that a movie featuring a female heroine scores 0 points on the Bechdel test.

Another interesting observation: Despite a whole host of powerful female characters, the Lord of the Rings trilogy gets pummeled (1 out of 3 points) and the scene in Return of the King where Eowyn arguably saves Middle Earth by defeating the Nazgul King while exclaiming “I am no man!” (she can kill him only because she is a a woman; see scene below) scores no points with the Bechdel test.

Basically, a wide range of movies where women are portrayed as powerful and in control of their destinies fail this test. Here’s but a few:

- X-men (Jean Grey and Storm to mention but a few)

- Superman (Lois Lane)

- The Dark Knight rises (Cat Woman)

- Hansel and Gretel (Gretel)

- Tomb Raider (Lara Croft)

- Avatar (Neytiri and Grace)

- Run Lola Run (Lola)

That seems strange to me.

So while there seems to be some validity to the test, it shows some strange results in practice.

What is still undeniable, however, is that there are more male protagonists in the movies. Why is that so?

Historical context

The role of women has historically been about nurture and the family sphere. There are good reasons for this. The male brain has much greater spatial awareness and our bodies are better at dealing with adrenaline and extreme physical conditions. In effect, we cope with hunting, hard labor and danger better than women.

Workplace death statistics (more than 90% are men) reflect this fact; men seek out the challenges and danger for which our physiologies are built. The woman’s brain, however, is much better at language, social interaction etc. In fact, women on average use three times as many words per day compared to men (20000 vs 7000).

These naturally occurring differences are the result of a co-created evolutionary process which has, among other things, ensured that pregnant women were sheltered from hard physical labor. (for a feminist who gets this, refer to Lauren Barnett’s presentation).

While the women were sheltered, men have historically been expected to provide that shelter. The ideals of the traditional male role are to serve, provide and protect. World mythology is overflowing with stories of men starting from humble beginnings, only to become a true hero after overcoming a series of trials. These tales – and acts – of heroism have brought solace and protection to those in need for milennia. Mythology expert Joseph Campbell calls this mythological theme the Hero’s journey.

There is something inherently exciting about the Hero’s journey. Most men I know feel a visceral bodily response when observing other men undertake acts of heroism. It’s what made Braveheart so impactful when I watched it in my teens. And women seem to find such men very sexy. (quote from a female friend: “I don’t like Mel Gibson, but William Wallace is super hot”).

The archetypal theme of the Hero’s journey has called many men to greatness. But it has a shadow side too; it has trained men to see themselves as expendable. The basic idea was this: As long as men died in service of a noble purpose, theirs was a fine death.*

So this is the bottom line: While women were expected to live limited yet relatively safe and social lives at home, men were given influence on the condition that they would sacrifice their lives in a heroic spectacle at the drop of a hat.

These are the tradeoffs inherent in the traditional gender roles.

*added 30. nov: The hero’s journey is really a metaphor for inner transformation. As such, it is an archetype that exists on all levels of development. Its themes have however exerted influence over the gender roles of society, and particularly those of the premodern era.

Understanding the mythical foundation of movies

Movies are the main propagators of mythological themes in today’s world. In the absence of stories around the fireplace and kids gathering at the feet of grandpa reading fairy tales in the flickering light of a lone oil lamp, we look to the silver screen for that essential soul food. The movies which make our spirit soar build on the same essential themes as humanity have grappled with for millennia: Survival in a dangerous world, truth, justice, purpose, faith, love.

These myths always involve a Hero’s journey of some sort, even the ones featuring women in leading roles (few characters in movie history are as heroic as Ripley in Aliens). They resonate in some deep part of us, where things still matter and there’s something worth dying for.

When you get that a majority of people still hunger for epic stories featuring danger and the overcoming of it, and you also get that this is what the male body is designed for, you will begin to understand why so many movies feature male instead of female characters.

Men leading, women following: Have movies lost touch with society?

As I make these observations, a question becomes pressing: Have these movies become outdated? Are they out of touch with the world we live in? The answer is: Possibly. It depends on our cultural perspective.

In parts of the world, the liberal West primarily, gender roles are changing and men are becoming sensitized and somewhat domesticated. Women, on the other hand, are becoming more agentic and autonomous. Women are clearly leading the way in this process; it’s as if the men have become sensitive because the women demanded it, not because the men wanted it.

In parts of the world, the liberal West primarily, gender roles are changing and men are becoming sensitized and somewhat domesticated. Women, on the other hand, are becoming more agentic and autonomous. Women are clearly leading the way in this process; it’s as if the men have become sensitive because the women demanded it, not because the men wanted it.

These changes are made possible thanks to huge changes in the techno-economical structures of society; in a service and information-based economy, career success does not involve risking my life at work.

In the conservative Western world and most of the rest of the world, however, traditional gender roles still prevail.

Let this much be clear: I would rather live in the liberal West than elsewhere. And I think it’s tremendous that we are encouraged to have more emotional range as individuals in this postmodern era (Spiral Dynamics green meme). But have you noticed, as I have, that most people who live in this cultural context seem a little bored? It’s almost as if nothing is at stake, everything is safe and comfortable. Life runs on auto-pilot. Despite all this emphasis on individual expression, things seem awfully flat.

Life-affirming qualities like vitality, passion and creativity have pretty much been erased by a postmodern crusade over the last several decades. Just look at postmodern art; often little more than ugly objects with some fancy conceptual description on a plaque. Pardon me for saying it, but most of it seems like pretentious crap. Beauty seems to have no inherent value anymore. Flying the banner of relativism, humanism and multi-culturalism, postmodernism has successfully wiped out all truths and absolutes. Without reference points to navigate by, life has become somewhat meaningless. It seems that these days, it doesn’t matter if what we say is true or meaningful, as long as we are expressing something. Look no farther than reality TV for what I’m talking about.

It’s as if the liberal West is held hostage by this pervasive meaninglessness. And men in particular seem affected. They’re becoming apathetic and impotent, in a double sense of the word. They’re dropping out of school, becoming losers in the workplace. It’s so epidemic that journalist Hanna Rosin is talking about “The End of Men”.

So for those of us who live in the liberal West, the theme of these movies may indeed be outdated. And yet, their success at the box office shows that even in this gender neutral postmodern era, the need for mythical stories of archetypal men and women still linger. I think the fact that they are “outdated” is exactly why they are popular. Once the politically correct police has gone home, people yearn for a different world, one where things matter, where people are loyal, have substance, integrity and dare to stand for something.

Introducing a new test

While the Bechdel test is great at pointing out how common it is for women in movies to be stuck in traditional gender roles, it doesn’t come with a multi-faceted and intelligent context within which to interpret the results. Accordingly, the people who use it often conclude that the marginalization of women is tantamount to discrimination, not realizing that the themes which they are critiquing are the very themes which contributed to making possible their modern lives of comfort.

To make my point more explicit, I have decided to design a male equivalent of the Bechdel test. It targets two primary facts of the male role:

- There are twice as many women as there are men in our genetic ancestry. Many men of history lived lonely lives without a woman to carry his child.

- Men’s lives are expendable.

A movie fails this brand new “Masculinity-Movies.com test” if it has a leading male role who:

- Is risking his life in order to serve/protect

- Is risking his life in service of truth and/or justice

- Is risking his life/wellbeing in order to make it in the world/“become successful”

- Is jumping through hoops to get the girl

Now, with the introduction of this test, we can join in with the women and point to movies and go “ooooh, traditional gender roles!”

Here are the movies on my site which pass this test:

That’s 5 out of 41 movies – about 12% – and most of them are debatable. In other words, my test used against the archived reviews yields far worse results than the Bechdel test does.

Which begs the question: Why aren’t you complaining, men?

Why men aren’t complaining

So women are stuck in traditional gender roles in a majority of movies… check! And using the new test I just created, we can easily see that an even greater majority of movies features men in traditional gender roles. Surprising?

If the Bechdel test and feminism form our lens, we might be upset that a movie like Saving Private Ryan fails it. Complaining about a lack of women, we may pay little attention to the extraordinary suffering men go through in the movie in service of the women and children who are at home. It’s a telling sign of how blind postmodern thinking can make us.

When cinemas in Sweden now introduce the Bechdel test, it’s because they take it for granted that women should now be portrayed in a more postmodern light – free to do what they want, self-expressed and not limited by their traditional gender role. In other words, the women of Sweden should move on from traditional to postmodern gender roles and so should the movies they watch.

And since fewer are arguing a similar case for men, I can only assume that it’s because it’s not as big of a deal that men are stuck in their traditional gender roles. In effect, women are invited to the evolutionary process while it’s sort of handy that a large part of the men don’t come along. If they did, they might change their minds about dying at work and then civilization would start crumbling as communications towers fell into disrepair, resources stopped getting mined, nuclear plant meltdowns did not get attended to etc.

Society needs men who are willing to pay the ultimate price. And if we start talking men out of that, perhaps by making movies that pass the test I just designed above (oops), civilization as we know it would collapse. It’s not pretty, but it’s the truth.

Conclusion

For fear of repeating myself, the Bechdel test does a great job of identifying movies featuring women in traditional gender roles. It does a terrible job of identifying movies in which women are being discriminated against, however. It requires a special kind of postmodern thinking to assume that the two are synonymous, which I hope I have done an adequate job of explaining to you.

If the people who complain about movies using the Bechdel test would instead proactively contribute to making the postmodern movies they want, maybe things would look differently. But I don’t think they will anytime soon. Because frankly, the world looks a lot more boring from this gender neutral place. There are no epic storylines that play out in a postmodern context. The postmodern imperative is, somewhat crudely put, to complain, not to make art. It doesn’t sell at the box office.

Beauty arises in the dance of polarity. It arises in the longing for merging with something that feels “other than” and the alluring promise that this Other is our long-lost portal to Oneness. This is the yearning that has inspired poets since the dawn of time, be it for an idea, a woman or God. When that polarity is deconstructed, so is beauty, meaning, purpose. And men without purpose wither and die.

Use the Bechdel test all you like. It serves a purpose. But realize that its purpose will forever be to point towards more postmodern gender roles, and for women only. If that’s what you want, then so be it.

But if you, like me, are bored with that and instead are yearning for a world in which we dare synthesize old with new, masculine with feminine, in a genuine life expression free from traditional stereotypes and postmodern ideology, then you’ll turn your back on it and maybe find, as you turn, that in the place you dared not look, true art awaits.

Discuss the article below: