An introduction to Gnosticism

by Peter Kessels

When Eivind visited me at my home in Weert, Netherlands in May of 2010, we watched The Last Temptation of Christ together. Eivind was working on a review of the movie at the time and as we share a growing interest in archetypes, mature masculinity, and mysticism, it inspired a good dialogue between us about the movie. I was inspired to take up my research on Gnosticism as a result and when Eivind asked me to write an introduction to this ancient Christian mystical tradition, I took him up on the offer.

In their seminal work on the KWML archetypes, Robert Moore and Douglas Gillette mention the Gnostics as prime examples of the Magician archetype. The KWML archetypes are an evolution of the breakthrough work on archetypes done by Jung almost 70 years earlier, whereas Jung in turn took his original ideas from Philo, a Gnostic who lived 2,000 years ago. In observing this historical lineage, we see that core themes of our contemporary men’s movement is based on the 2000-year old gnostic tradition. Who were these early pioneers of psychology, mathematics, philosophy and spirituality? Let’s find out.

In this article, I adopt the definition of Gnosticism as introduced by Timothy Freke and Peter Gandy, who describe it as an attitude towards life and spirituality, which is opposed to Literalism. This way, any individual’s spiritual practice can be seen somewhere on the spectrum between these two poles. A person on the Literalist end of this spectrum would see his Scriptures as the word of God, place value on the outer aspects of his religion’s teachings, initiation myths and rituals. He sees his own religion as offering the Truth while other religions do not, and will go to war if his belief system comes under threat. A Literalist identifies with the collective with which he shares his beliefs.

Gnostics, however, see the words in the teachings, parables and myths as pointing to something beyond their common meaning, to something which paradoxically cannot be captured in words, to the ineffable Mystery. They see themselves on a journey of personal transformation, and accept truth from any source. They follow their hearts, not the herd. Gnostics are free spirits consumed by their own private quest, not by the goal of recruiting more adherents to a religion.

This definition of Gnosticism is different from what most scholars use, and the reason I adopt this definition is because it is actually useful. Rather than making a distinction between different religions, we’ll look at different attitudes which occur within every one of those religions. What we then see, is that a Christian Gnostic is closer to a Muslim or Buddhist Gnostic than to a Christian Literalist. Throughout history, intolerant Literalists have brutally oppressed Gnostics, while the opposite never occurred. In the West, the Literalist Roman Catholic Church has eradicated gnostics, a crime from which we still haven’t recovered; since the Gnostics were the carriers of wisdom and research of their time, an incredible wealth of knowledge and literature has been destroyed.

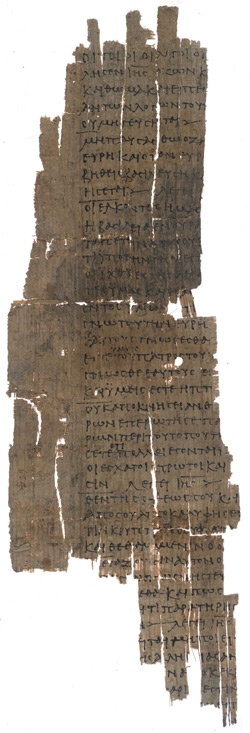

In 1945, Christian gnostic texts (along with works by Plato) were found at Nag Hammadi in Egypt. The farmer who found them by accident subsequently destroyed some of them and sold the rest, not realizing what treasure he had unearthed. After all the surviving texts were gathered, translated and interpreted, a process which has taken 30 years, scholars have shed new light on the origins of Christianity, enabling an interpretation of the gospels which is radically different from what the Literalist Churches have been trying to tell us.

Christian Gnostics were political radicals who preached liberty, equality and brotherhood centuries before the French Revolution. The first Christian monasteries where egalitarian communities, where property was held in common and women were treated as equals. It was the accepted practice for male Christian Gnostics to travel with a female spiritual partner, whom they referred to as “sister-wife”. While some schools were ascetic in nature, some saw sexuality as a celebration of the union of God and Goddess, from which all life springs. They are said to have sometimes practiced sacramental nudity in church and even ritual intercourse. The Literalist Epiphanius desribes his experience as a young man of 20, meeting two pretty Gnostic women who invited him to one of their agapes or love feasts, which turned out to be an orgy. With the horror characteristic of the deeply repressed, Epiphanius was outraged that these Gnostics believed that they ‘must ceaselessly apply themselves to the mystery of sexual union’.

Ibn Arabi, a Sufi known as the Great Master, believed that women were a potent incarnation of Sophia – the Goddess Christianity once had but lost (the deity in Abrahamic religions rules alone) – because they inspired in men a love that was ultimately directed towards God. Like the libertine Christians, he venerated sex as a spiritual practice which could help human beings participate in the cosmic sexuality through which the Mystery knows itself. He even translated a Sanskrit scripture on Tantric Yoga into Persian!

Not all Gnostics were such party animals, however, and this touches upon the core of Gnosticism: spirituality is a personalized affair, and individualism is key. Instead of dogma, initiates are put on a path of self-discovery, leading through different stages of initiations, and the ultimate goal is to achieve gnosis: direct experience of the Mystery. The early Christian Gnostics recognized that different people had different levels of awareness, which they divided into hylics, psychics and pneumatics.

In Greek, hyle means matter, and hylics is a term for people who regard values as material: as things handed to them from an external source. With this conviction, the hylic has cut himself off from his own compassion as the source of all values. For this reason, the Gnostics see such a person as lost: he does not know where he came from, nor where he is going. He has lost his inner compass. The gnostic Valentinus called this aporia, which means confusion. For a hylic, any felt sense of compassion which doesn’t fit within his own convictions is experienced as evil temptation. This is why a hylic is always at war with himself: his inner world is his enemy.

A psychic is in contact with his compassion, but does not act on it. It’s the attitude of the rationalist: feelings are irrational and therefore unreliable. Peace of mind is reached only by freeing yourself from desire. Gnostics reject peace of mind as the goal of a spiritual life. If you want to let love play a role in your life, you will have to be prepared to be vulnerable, to let it cut into your soul, and therefore to allow your piece of mind to be disturbed. A psychic, however, thinks he can liberate himself from suffering. He continually attempts to tame his soul until it is silent. Like the hylic, a psychic has made is inner world into an enemy.

For the Gnostics, the pneumatic was the idealized type of person: a human being who has inner freedom, and who is motivated by love. Pneumatics experience love as the source of all compassion. Love is fundamentally different from the solidified faith of the hylic and the peace of mind of the psychic. The core of the gnostic way of life is that love can only blossom in total openness to all that is. Only a person who has made peace with himself, who has stopped to fight himself, can obtain this level of openness. In practice, this means that you disarm yourself, take off your armor, and that you are prepared to be touched, even by pain and sorrow.

The Christian Gnostic schools used to let anybody enter who wanted to do so, but they had different levels of initiation. Psychics were taught the Outer Mysteries, and had a literal interpretation of the gospels. For this purpose, the gospels were written as stories designed to draw people in, and to be used as reminders of what was expected of initiates (with Jesus being a prime example). The Roman Catholic Church (and all later deviations) were based on these outer, or exoteric, teachings. These same gospel stories, however, had other hidden meanings as well, sometimes even with multiple layers. These hidden meanings were only revealed to people who had grown into the pneumatic stages. These were completely different from the literal interpretation, but have been repressed by the Church. When the Roman empire needed a single religion to unite the empire, exoteric Christianity was used for that aim. Maybe it was too hard to build a power base on the esoteric parts? Alas, the Gnostics were thereafter made into heretics – their wisdom was lost – and the Dark Ages began.

The Gnostics were way ahead of their time, and their teachings couldn’t get a foothold in these early days. It is only in recent times that it has become safe to practice it freely and so the path has been cleared, making the resurrection of this mystical tradition in modern form possible. By entering the gnostic path of self-knowledge, you are stepping into a long lineage of great men, from Plato to Plotinus to Jung. Gnosticism is a path to authenticity, love, compassion and enlightenment and we find echoes of it in such contemporary men’s movements as The Authentic Man Program. It looks like its time has finally come.

Discuss the article below: