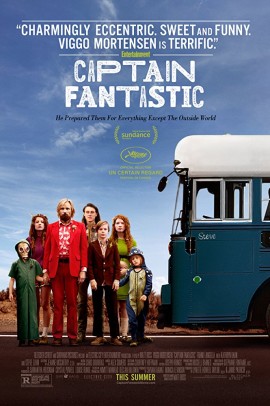

Captain Fantastic (2016)

Synopsis

In the forests of the Pacific Northwest, a father devoted to raising his six kids with a rigorous physical and intellectual education is forced to leave his paradise and enter the world, challenging his idea of what it means to be a parent.

| Genre | Drama, Comedy |

| Production year | 2016 |

| Director | Matt Ross |

| Male actors | Viggo Mortensen, George MacKay |

Title missing

by Kevin Latham

King on the Mountain

Reigning supreme within this wooded mountain enclave, Ben’s figurative hippie battle-bus is occupied by almost every archetypal passenger imaginable – he is Father, Rebel, Trickster, Hero, Wild Man, Warrior, Lover, Magician and King. And a good king he is too, for the most part – ruling his realm with a benevolent spirit, a strong hand and a certain worldly wisdom. We see, however – as the film progresses – that in spite of his many noble traits, aspects of his kingdom (both internal and external) have been neglected – causing great strife for both his subjects and for Ben himself.

From the outset it is evident that Ben and his wife, Leslie, have achieved something extraordinary – raising six remarkable children who are as confident and intellectually sophisticated as they are practical and athletic. The opening scene, in which eldest son, Bodevan, engages in a singularly brutal and beautiful initiation into manhood – stalking and slaying a deer armed only with a short blade – demonstrates that the family have successfully re-assimilated aspects of our ancestral heritage into their daily lives.

This savage rite – complete with a ceremonial feasting on the animal’s still-oozing heart – is immediately contrasted with tender moments as family members play in a stream, bound through unkempt meadows and fulfil the many tasks required to live a rugged existence in symbiosis with the land. The tranquillity of this idyllic Eden – a paradise in which the junior Cashes enjoy an irregular but untarnished innocence – is shattered, however, when they discover that their mother – their Eve – has committed suicide.

Thus begins our hero’s journey, as Ben and family board their battle-bus (bearing the unassuming moniker, ‘Steve’) intent on resting her spirit from the clutches of their tyrannical grandfather, Jack, who is determined to keep Ben from her funeral and unwilling to respect his daughter’s final wishes. Beset by challenges – the ‘liberation’ of food from a supermarket, the bamboozling of a cop who threatens their familial sovereignty and a stark confrontation with the vacuous reality of modern economic and social life, the family engage in a voyage of self-discovery that is frequently as hilarious as it poignant.

Nature Abhors a Vacuum

To my mind one of the film’s most thematically significant scenes focuses upon Ben’s attempts to buoy his children’s spirits by shunting forwards the celebration of their hallowed ‘Noam Chomsky Day’ – a jubilant chrimbo-esque occasion that celebrates the achievements of the prolific academic and peace activist. Being a bit of a Chomsky-cheerleader myself, I’m inclined to agree with Ben’s characterisation of the man – as a “humanitarian who has done so much to promote human rights and understanding”.

The elevation of the uber-analytical scholar to deific status does demonstrate our desperate need for idols infused with archetypal energy, however. Where the ‘gods’ of old are spurned and torn from their plinths, new effigies are installed in their place to fill the void created by their absence.

Ben’s son, Rillion, recognises a fundamental flaw inherent in this trend – one that he understands intuitively but struggles to articulate rationally (as is so often the case when people of faith attempt to justify their visceral standpoints to those who demand corroborative evidence for them). His desperate plea to embrace some semblance of normality:

“Why can’t we celebrate Christmas like the rest of the entire world?”

Could easily be read as a lazy unwillingness to engage in independent thought and action; but I don’t think that that’s an accurate assessment of his inclinations.

On the contrary, this temperamental teen instinctively recognises that the value of celebrating a festival such as Christmas – along with its superficially archaic poster-boys (whether we’re talking JC or the big guy in red) lies not so much in the particular religious symbolism associated with these archetypal brands – but the fact that its shared by the rest of the tribe. These rituals connect us to other people – past and present – they afford us a sense of community and continuity, and when we abandon them to venerate our own personal gods and observe exclusive rituals, we run the risk of isolating ourselves from the collective activities which instil our lives with meaning.

Which is not to say that this is necessarily all bad – after all, every existing religious or ideological tradition was established by small groups of people who penned new narratives when older stories ceased to serve their contemporary needs. I do think, however, that we need to be very wary of throwing the baby out with the bathwater – the Christian faith preserved much of the archetypal meat served up by the pagan traditions that preceded it, after all.

A Tale of Two Knights

Rillion’s role as boyish agitator and challenger to his father’s supremacy has already been established, but I’d like to explore Ben’s shortcomings further by focusing on his relationship with each of his sons, Rillion and Bodevan. As Red and White Knight’s, these two inexperienced warriors (note, it is the two masculine heirs who challenge the authority of their father) lay bare both Ben’s successes and his failures.

Within the storytelling traditions of Europe, these two colours/tones were used to denote specific stages within a man’s development. The red represents youthful vigour – and draws its power from emotional engagement, the desire to assert one’s independence and to achieve the personal objectives of its standard-bearer.

The elder White Knight possesses the patience and self-restraint of an older man/adolescent, and directs his attention away from personal desires and towards loftier ideals; but he remains naïve until he has confronted the shadow aspects of his nature and integrated them into his psyche (at which point he becomes the Black Knight – a fully mature man with all archetypal resources at his disposal). The fact that Bodevan embodies the traits of the White so fully at such a tender age does demonstrate Ben’s accomplishments as a father, however – and the policy of honesty the latter adheres to in his children’s presence appears integral to their development.

Nonetheless, enraged by his father’s perceived failings as a king – and the toll he feels that they took upon his mother – Rillian rebels against his rule:

“Dad made her crazy. Dad’s dangerous. You think our lives are so great – you think dad’s so perfect!”.

And here, Rillian’s Red Knight call’s Bodevan’s White counterpart to action – revealing that with his mother’s help, he has been ‘plotting’ to flee his father’s kingdom; applying to University in order to embark upon a hero’s journey of his own.

Pressed by his father, who cannot understand his son’s need to beat his own path through the under-brush, his eldest rages:

“I know nothing!… I’m a freak because of you. You made us freaks. And mum knew that. She understood. Unless it comes out of a book I don’t know anything!”.

The Great Mother has access to intuitive wisdom and a capacity for flexibility that the masterful King does not naturally possess – and without her influence the children may be crushed by the weight of his iron hand. Bodevan’s romantic encounter with the feisty, streetwise Clare – ‘the woman with the golden hair’ (an archetypal figure that stirs expressive Lover energy within a man, illuminating another layer of masculinity within him) has, however, highlighted both his own naivete and that of his father.

The Battle of Two Kings

Jack, on the other hand, is everything that you might expect of a late-twentieth century fictional father-figure. Rigid, ruthless, content to suppress the maternal spirit of his own queen (his wife – who for her part makes every effort to reconcile the estranged family) and insistent that his own conservative traditions be observed – despite the fact that they reflect neither his daughter’s wishes nor her idiosyncratic nature.

He’s the typical ‘dark father’ of the West – preoccupied with wealth and status, emotionally repressed, excessively controlling – and a lesser movie would have left it there. Captain Fantastic, on the other hand, proves its chops by bestowing a soul upon this authoritarian patriarch; serving us not with a monster to loathe or a pantomime villain to jeer at, but with an essentially decent – if deeply flawed – individual that requires a great deal more consideration to understand.

We see that far from being driven exclusively by egotism and self-interest, his actions are motivated by the tremendous grief he feels at the loss of his daughter and the love he feels for the rest of his family. The scenes in which Jack plays with his grandchildren – thawing his seemingly crystalline heart in the process – are amongst the most subtle and touching in the entire movie.

When Ben concedes defeat to the elder Jack (recognising his mistakes and the fact that his demanding parental decrees are exposing his offspring to unnecessary danger) the latter even manages to extend to him both a literal and figurative fatherly hand. This is a truly wonderful moment in which veteran actor, Frank Langella, floods the ritual space between them with a gentle beneficence.

What’s more, his loosing of an arrow upon Ben (“if I’d meant to hit you, I’d have hit you”) – is impregnated with a rich and potent symbolism. On the one hand, it demonstrates the necessity for a decisive intervention by an elder Warrior to redirect the flow of the narrative – and their family’s fortune. On the other, the arrow’s sudden ‘THWACK’ and the reveal that Jack is himself a gifted archer suggests that these two duelling bucks – seemingly of entirely unrelated species – are not so different after all.

Conclusion: Mission Complete

Having made peace with the Kingdom over the hill (but resisting attempts by its ruler to keep them there) it now falls to the family to ‘complete their mission’. And so they set about rescuing their mother’s body from a unfitting fate and giving her the send off she deserves (the values of our heroic entourage must be tempered with an understanding and acceptance of other people’s, but not abandoned altogether).

It’s this heart-warming scene (following a cheery spot of grave-robbing) which demonstrates that balance has been restored to the family’s world. Their rustic rendition of Guns & Roses’ Sweet Child of Mine seamlessly blends the contemporary with the tribal – whilst lauding the creative expression of the individual (not least when Leslie’s cremated ashes are unceremoniously flushed down the toilet!).

So, what do we take from this pithy but whimsical affair? In some respects the titular Captain’s call to action is very different from the journey required of most of us – already intimately connected with his primal instincts, his challenge is to become more domesticated – to adopt a more contemporary sensibility (which is represented symbolically by Ben’s shaving of his beard – the civilising of his hairy native).

For many men the opposite is true, and this Wild Man’s comparatively feral existence stirs within us a wholly appropriate longing for a return to a simpler – and more calloused – mode of being. In other respects, however, the film speaks directly to the postmodern man – it being a clarion call to put the needs of others before our own, to forge stronger bonds with extended family and to lower our drawbridge, so that we may reconnect with the diverse community that lies beyond our castle walls.

This is what I love most about this delightful yarn – it challenges us to seek out and assimilate the very best from the old world and the new. Reeling with motion sickness induced by the frenetic rate of change in our society, it’s often easy to forget how blessed we are to be living through such extraordinary times.

Every (Western) man has the world at his finger tips – we sail a vast techy sea of information that we can fish for nutritious bites whenever we choose. Alternatively, we can plonk ourselves down in any of a dozen wildernesses within easy reach of our homes by simply hitting the accelerator or boarding a plane. The key to carving out a better future for ourselves is to incorporate each of these two experiences cohesively within our psyches. This is, I would suggest, the challenge of our times – and it’s one that I intend to meet with all my manly vigour.

So gents, I implore you to sharpen your knives and your I.T skills – because the Cap’ wants you to know that you needn’t choose between the two. You can have your venison and eat it – just so long as you’re willing to hunt, chop, whittle, laugh and learn as tribe. This world’s a tough old place, but as Rillian states (quoting the shrewd Chomsky):

“If you assume that there is no hope, you guarantee that there will be no hope. If you assume that there is an instinct for freedom, that there are opportunities to change things, then there is a possibility that you can contribute to making a better world”.

I suggest that each of us follow Ben’s example, and strive to make of it all that it can be.